When a patient takes a pill that contains two drugs in one dose-like blood pressure meds combined with a diuretic-that’s a fixed-dose combination (FDC). These aren’t just convenient. They’re critical for managing chronic conditions like HIV, diabetes, or asthma. But getting a generic version of these combo products approved? That’s where things get messy. Unlike a single-drug tablet, where bioequivalence is straightforward, combination products come with a host of hidden problems that can stall approval for years.

Why Bioequivalence Isn’t Simple for Combo Products

Bioequivalence means proving that a generic version performs the same way in the body as the brand-name product. For a single-drug pill, you give it to 24 healthy volunteers, measure how much drug enters the bloodstream, and check if the generic’s levels fall within 80-125% of the original. Simple. Clean. Repeatable. But when you combine two active ingredients in one tablet, capsule, cream, or inhaler, things change. The two drugs might interact. One could slow down the absorption of the other. The coating that controls release might affect how both drugs dissolve. Even the way the ingredients are mixed can alter how they behave in the gut, skin, or lungs. The FDA now requires generic makers to prove bioequivalence not just to the combo product itself, but also to each individual drug given separately. That means running three-way crossover studies-where volunteers get the brand combo, the generic combo, and the two drugs taken apart-all in random order. These studies need 40 to 60 participants, not 24. They cost more. They take longer. And they’re far more likely to fail.Topical Products: The Invisible Delivery Problem

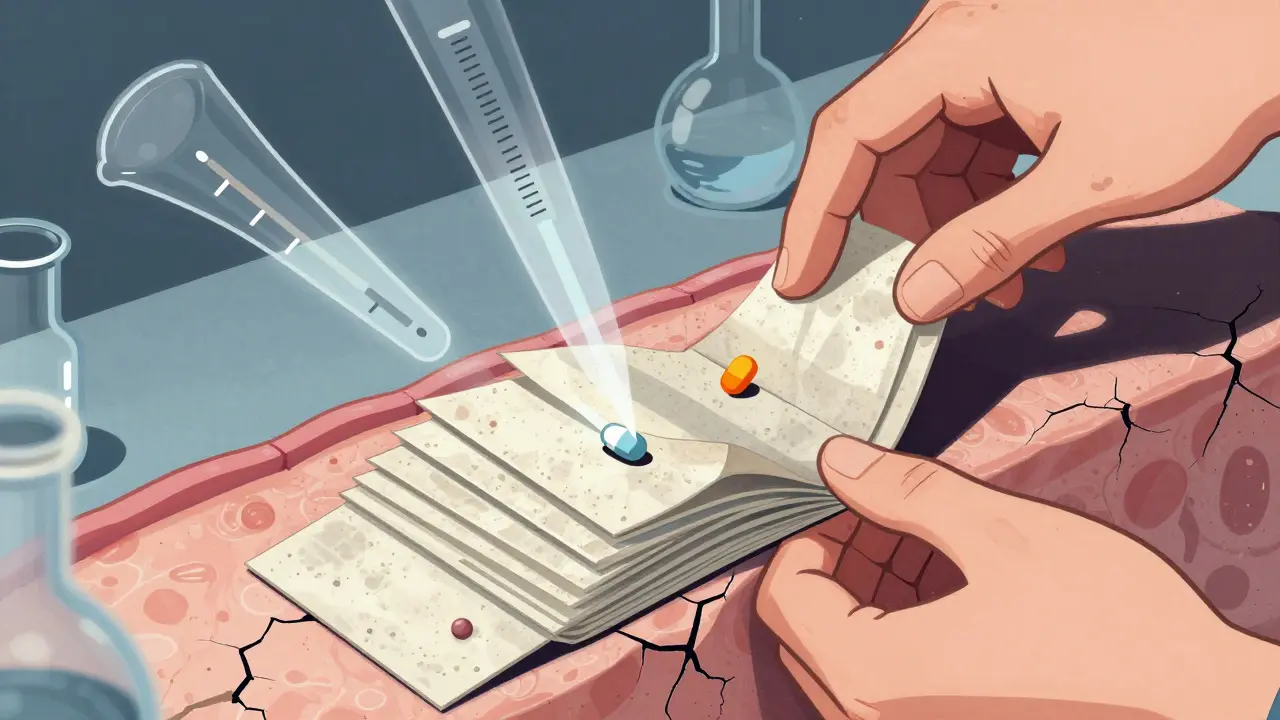

Creams, ointments, and foams for eczema, psoriasis, or fungal infections are among the hardest to test. You can’t just swallow a cream and measure blood levels. The drug needs to reach the top layer of skin-the stratum corneum-to work. But how do you measure that? The FDA’s current method? Tape-stripping. You press adhesive tape onto the skin, peel it off, and repeat 15 to 20 times to collect layers of skin cells. Then you analyze how much drug is in each layer. Sounds precise, right? It’s not. There’s no standard on how deep to go, how much tape to use, or how to handle differences in skin thickness between people. One lab’s results can vary wildly from another’s. Some companies have tried clinical endpoint studies-measuring actual skin improvement in hundreds of patients. But those cost $5 million to $10 million per trial. Most generic companies can’t afford it. That’s why many topical generics never make it to market, even when the active ingredients are identical.Drug-Device Combo Products: It’s Not Just the Drug

Inhalers, auto-injectors, and nasal sprays are called drug-device combination products (DDCPs). Here, the device matters as much as the drug. A generic inhaler might contain the exact same medicine as the brand, but if the valve, nozzle, or button feels different, patients might not inhale deeply enough. Or they might press too hard. The result? Less drug reaches the lungs. The FDA now requires testing of aerosol particle size distribution. For a generic inhaler to be approved, its particle size must be within 80-120% of the brand. But even that’s not enough. A 2024 FDA workshop found that 65% of rejection letters for DDCPs cited problems with user interface-not the drug, not the device alone, but how the two work together when a person uses them. One company spent three years trying to get a generic epinephrine auto-injector approved. Each version passed lab tests. But when real patients used them, many didn’t trigger the device properly. The button needed more force. The safety cap was stiffer. These tiny differences made the difference between life and death in an emergency. The product was pulled.

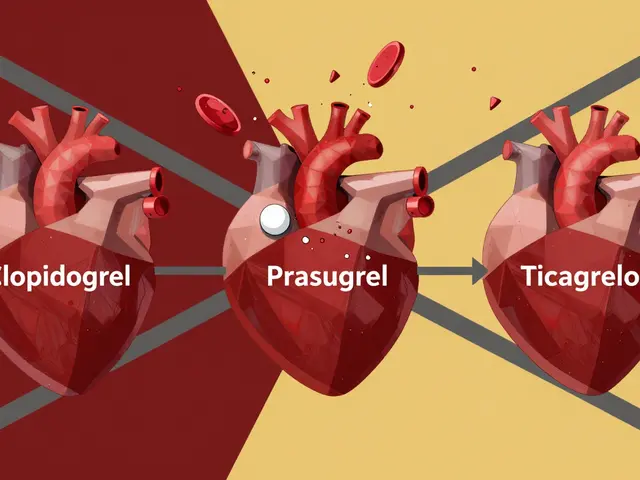

Modified-Release Formulations: The High-Stakes Game

Drugs that release slowly over time-like extended-release painkillers or heart medications-are especially tricky. If the generic releases the drug too fast, it can cause side effects. Too slow, and it doesn’t work. For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-where the difference between a helpful dose and a toxic one is small-the acceptable bioequivalence range tightens from 80-125% to 90-111%. That’s a much narrower window. And failure rates? Up to 40% for initial submissions, according to the FDA’s 2023 report. One generic maker spent $18 million trying to launch a modified-release FDC for hypertension. The first three batches failed bioequivalence tests because the coating degraded differently in the stomach. The fourth batch passed-but only after switching from a polymer blend used in the brand to a completely different one. The FDA approved it, but the company lost two years and half its R&D budget.Why So Many Generic Companies Are Struggling

The numbers tell the story. Teva reported that 42% of their complex product failures were due to bioequivalence issues. Mylan (now Viatris) said development timelines for topical combos jumped by 18-24 months. A 2023 survey of 35 generic companies found 89% thought current bioequivalence rules for combo products were “unreasonably challenging.” Small and mid-sized firms are hit hardest. Setting up a lab with LC-MS/MS equipment costs $300,000 to $500,000. Hiring scientists trained in complex pharmacokinetics takes years. And even then, regulatory feedback is inconsistent. One FDA division might accept a certain method; another rejects it. Industry submissions to the FDA’s public docket show 78% of companies cite “lack of clear bioequivalence pathways” as their top barrier.

What’s Being Done to Fix This

The FDA isn’t ignoring the problem. Since 2021, it’s run the Complex Product Consortium, which has developed 12 product-specific bioequivalence guidelines. Companies that follow these get their approvals 8-12 months faster. New tools are emerging. Physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling lets companies simulate how a drug behaves in the body using computer models. Seventeen generic products have been approved using this method since 2020. It cuts clinical testing by 30-50%. The FDA is also working with NIST to create reference standards for complex products. By late 2024, they’ll release standardized samples for inhalers-so labs everywhere can calibrate their equipment the same way. That should reduce variability between testing sites. And in 2024, the FDA announced a “Bioequivalence Modernization Initiative” aiming to create 50 new product-specific guidances by 2027. The first focus? Respiratory products, where 78% of submissions currently fail bioequivalence checks.The Bigger Picture: Why This Matters

Combination products make up 38% of the global generic drug market-$112.7 billion in 2023. But approval times are nearly three times longer than for simple generics: 38.2 months versus 14.5 months. That means patients wait years longer for affordable options. Patent thickets and litigation delay entry even further. DDCP legal battles rose 300% between 2019 and 2023, pushing generic launches back by an average of 2.3 years. If these challenges aren’t solved, 45% of complex brand products may have no generic competition by 2030. That’s billions in unnecessary spending by patients and healthcare systems. The U.S. saved $373 billion on drugs in 2020 thanks to generics. But that number could be much higher-if we could get complex generics to market faster.What’s Next for Generic Developers

If you’re developing a combination product, don’t wait until you have a finished formulation to talk to the FDA. Type II meetings-early consultations-are up 220% since 2020 for a reason. Use them. Ask for feedback on study design before you spend millions. Consider PBPK modeling early. It’s not magic, but it’s becoming a required part of the conversation. Build relationships with labs that specialize in tape-stripping or aerosol analysis. Don’t assume your in-house team can handle it. And if you’re a patient or provider: ask if a generic version of your combo drug exists-and if not, why. The delays aren’t just bureaucratic. They’re financial. They’re personal. And they’re preventable.What is a fixed-dose combination (FDC) product?

A fixed-dose combination (FDC) is a single medication that contains two or more active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) in a fixed ratio. Examples include HIV treatments like dolutegravir/lamivudine, or hypertension drugs like amlodipine/valsartan. FDCs simplify dosing, improve adherence, and are common for chronic conditions.

Why is bioequivalence harder to prove for combination products than for single-drug products?

Single-drug bioequivalence only requires measuring one active ingredient’s absorption. For combination products, you must prove each drug reaches the bloodstream at the same rate and extent as the brand-and that they don’t interfere with each other. This often requires complex three-way crossover studies, larger sample sizes, and advanced analytical methods, increasing failure rates by 25-30%.

What makes topical combination products so difficult to test?

Topical products like creams and foams deliver drugs through the skin, not into the blood. The FDA uses tape-stripping to measure drug levels in skin layers, but there’s no standard for how many layers to collect or how to analyze them. Results vary between labs, and clinical endpoint studies-which track skin improvement-are too expensive ($5-10 million) for most generic makers.

Why do drug-device combinations like inhalers face unique bioequivalence challenges?

Even if the drug is identical, differences in the device-like button pressure, nozzle design, or aerosol particle size-can change how much medicine reaches the lungs. The FDA requires aerosol particle size to stay within 80-120% of the brand. But 65% of rejection letters cite user interface issues, not drug content. A generic inhaler that feels different to patients may be used incorrectly, reducing effectiveness.

How are regulatory agencies responding to these challenges?

The FDA launched the Complex Product Consortium in 2021 and has created 12 product-specific bioequivalence guidances. It’s also developing reference standards with NIST and promoting PBPK modeling to reduce clinical testing. The 2024 Bioequivalence Modernization Initiative plans to release 50 new guidances by 2027, starting with respiratory products. The EMA still requires more clinical data than the FDA, creating duplication and higher costs.

What role does PBPK modeling play in bioequivalence testing?

Physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling uses computer simulations to predict how a drug behaves in the body based on its chemical properties, formulation, and human physiology. It’s been accepted in 17 FDA-approved generic applications since 2020. When validated, PBPK can reduce the need for clinical bioequivalence studies by 30-50%, saving time and money for developers.

What’s the financial impact of delayed generic entry for combination products?

Delayed generic access costs the U.S. healthcare system billions. In 2020, generics saved $373 billion. But complex products take nearly three times longer to approve-38.2 months vs. 14.5 months. If bioequivalence hurdles aren’t solved, 45% of complex brand products may have no generic competition by 2030, leaving $78 billion in sales without affordable alternatives.

Honestly, this is one of those topics that flies under the radar but impacts real people every single day. I’ve got a friend on a combo med for hypertension-generic version took 4 years to hit the market. Four years. She was paying $800 a month until then. This isn’t just regulatory bureaucracy-it’s people skipping doses because they can’t afford it.

January 18Lydia H.