Breathing Symptom Checker

Check Your Symptoms

Answer these questions based on your current or recent symptoms. This tool is not a medical diagnosis but can help identify when to seek professional care.

Your Results

When you hear the term breathing disorders is a group of conditions that impair the lungs' ability to move air efficiently, you might picture wheezing, coughing, or a gasp for air. The truth is a bit more layered - it’s a story of tiny sacs, muscle rings, and oxygen‑rich blood vessels all trying to keep you alive. This guide walks through the science behind that story, explains why common disorders happen, and gives you a practical checklist to spot trouble early.

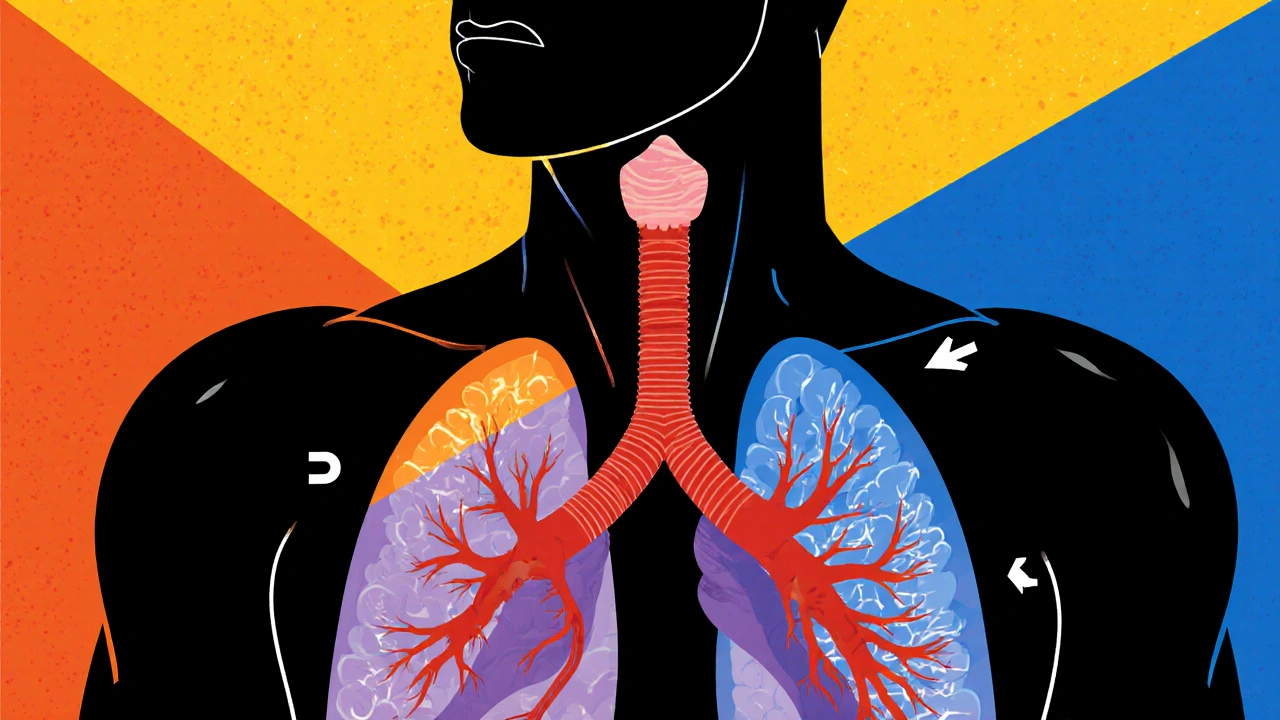

How Your Lungs Move Air

Lung is a pair of spongy organs that exchange oxygen and carbon dioxide between the air you breathe and the bloodstream. Air enters through the nose or mouth, travels down the trachea, and branches into two main bronchi. Those bronchi subdivide into smaller bronchioles, ending in millions of alveoli - tiny, balloon‑like sacs where gas exchange occurs.

- During inhalation, the diaphragm contracts, pulling down and creating negative pressure.

- Air rushes in, filling the alveoli.

- Oxygen diffuses across the alveolar wall into capillaries, while carbon dioxide moves the opposite way to be exhaled.

Any obstruction, inflammation, or scarring along this pathway can disturb the delicate balance, leading to the symptoms we label as breathing disorders.

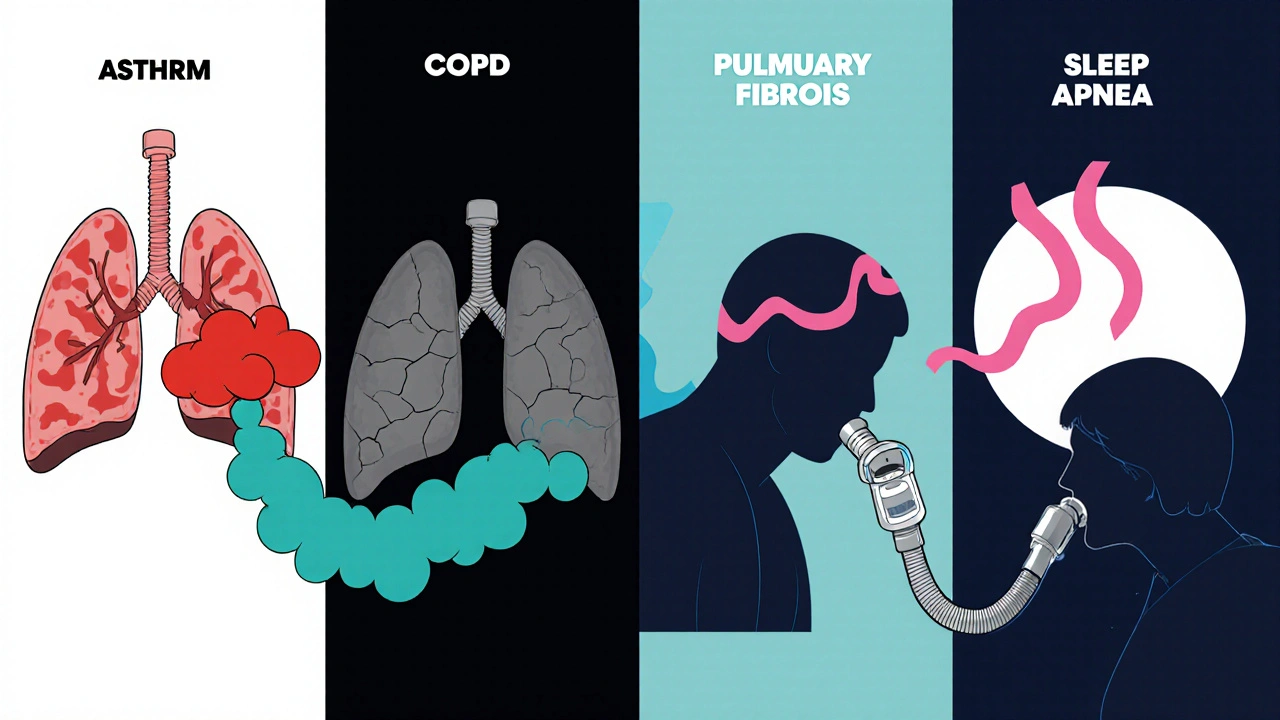

What Counts as a Breathing Disorder?

Medical professionals group these conditions by the part of the airway they affect, the underlying cause, and whether the problem is reversible. The most common categories include:

- Obstructive disorders - airway narrowing that blocks airflow (e.g., asthma, COPD).

- Restrictive disorders - stiffening of lung tissue that limits expansion (e.g., pulmonary fibrosis).

- Neuromuscular disorders - weak muscles or nerves that impede breathing.

- Ventilatory control disorders - brain‑stem signals go awry, causing sleep apnea.

Each type has a distinct physiological fingerprint, but they often overlap in real life, especially when smoking or chronic inflammation is involved.

Asthma: The Reactive Airways

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disease that makes the bronchi hyper‑responsive to triggers like pollen, cold air, or exercise. When exposed to a trigger, immune cells release histamine and leukotrienes, causing:

- Bronchial smooth‑muscle contraction (bronchoconstriction).

- Swelling of the airway lining (edema).

- Increased mucus production.

The result is a narrowed airway that stalls airflow, producing wheeze, cough, and shortness of breath. What’s unique about asthma is that the obstruction is at least partially reversible with bronchodilators - quick‑acting inhalers that relax the smooth muscle.

COPD: The Smoker’s Legacy

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease is a progressive, largely irreversible condition caused by long‑term exposure to irritants, most commonly tobacco smoke. COPD blends two sub‑conditions:

- Emphysema - destruction of alveolar walls reduces surface area for gas exchange.

- Chronic bronchitis - thickened mucus‑secreting glands clog the bronchi.

The combined effect is a loss of elastic recoil and airway narrowing that makes exhaling especially hard. Over time, patients develop a characteristic “barrel chest” as the lungs over‑inflate.

Pulmonary Fibrosis: Scarring Inside

Pulmonary fibrosis is a restrictive lung disease where scar tissue (fibrosis) thickens the walls of the alveoli and surrounding interstitium. The scar tissue stiffens the lung, limiting its ability to expand during inhalation. Common triggers include prolonged exposure to silica dust, certain medications, or autoimmune disorders.

Patients often notice a dry cough and a gradual decline in exercise tolerance. Because the scar tissue is permanent, treatment focuses on slowing progression and improving quality of life rather than reversal.

Sleep Apnea: When Breathing Stops at Night

Sleep apnea is a ventilatory control disorder where the airway collapses repeatedly during sleep, pausing breathing for seconds to minutes. Two main types exist:

- Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) - physical collapse of the throat muscles.

- Central sleep apnea (CSA) - brain fails to send proper breathing signals.

Repeated pauses lower blood oxygen, trigger rapid awakenings, and cause daytime fatigue. Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) machines keep the airway open by delivering steady air pressure.

Key Physiological Processes Behind Symptoms

Regardless of the specific disorder, three core mechanisms drive the symptoms you feel:

- Airflow limitation - narrowed or blocked passages increase resistance, making it harder to move air.

- Reduced gas‑exchange surface - damaged alveoli lower the area where oxygen can pass into blood.

- Impaired respiratory muscle function - inflammation or neurological issues weaken the diaphragm and intercostal muscles.

When any of these processes falter, the body compensates. You might breathe faster (tachypnea), feel a tight chest, or develop a bluish tint around the lips (cyanosis) as oxygen levels dip.

Quick Checklist to Spot a Problem

- Frequent wheezing or whistling sound when breathing.

- Persistent dry cough that worsens at night or after exercise.

- Shortness of breath during activities that used to be easy.

- Chest tightness or feeling “out of breath” after climbing a few stairs.

- Daytime fatigue despite adequate sleep (possible sleep apnea).

- Unexplained weight loss or fever (may hint at infection on top of a lung condition).

If you tick more than a couple of these boxes, it’s worth chatting with a GP or a respiratory specialist.

Managing the Conditions and When to Seek Help

Most breathing disorders benefit from a three‑pronged approach: medication, lifestyle changes, and monitoring.

- Medication - bronchodilators for asthma, inhaled steroids for COPD, antifibrotic drugs for pulmonary fibrosis, and CPAP for sleep apnea.

- Lifestyle - quitting smoking, avoiding known triggers, staying active with low‑impact exercise, and maintaining a healthy weight.

- Monitoring - peak‑flow meters for asthma, spirometry tests for COPD, and pulse‑oximeters at home for sleep apnea.

Red flag symptoms that need immediate medical attention include:

- Sudden, severe shortness of breath.

- Chest pain that radiates to the arm or jaw.

- Rapid, shallow breathing (respiratory rate > 30 per minute).

- Blue lips or fingertips.

These could signal a life‑threatening exacerbation or an infection requiring antibiotics or even hospitalization.

| Condition | Primary Issue | Typical Triggers | Reversibility | Key Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asthma | Bronchoconstriction & inflammation | Pollen, cold air, exercise | Partially reversible | Inhaled bronchodilators, steroids |

| COPD | Airway obstruction & alveolar loss | Long‑term smoking, pollutants | Mostly irreversible | Long‑acting bronchodilators, rehab |

| Pulmonary Fibrosis | Stiffening of lung tissue | Silica, meds, autoimmune disease | Irreversible | Antifibrotic drugs, oxygen therapy |

| Sleep Apnea | Airway collapse during sleep | Obesity, anatomical narrowing | Variable (often treatable) | CPAP, dental devices, weight loss |

Bottom Line

Understanding the science behind breathing disorders turns vague worries into actionable knowledge. By recognizing how the lungs work, what goes wrong, and which signs matter, you can catch problems early, choose the right treatments, and keep your breath steady.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between asthma and COPD?

Asthma is usually triggered by allergens or irritants and the airway narrowing can be reversed with medication. COPD, caused mainly by long‑term smoking, involves permanent damage to lung tissue and is largely irreversible.

Can breathing disorders be prevented?

Yes, avoiding smoking, reducing exposure to air pollutants, maintaining a healthy weight, and managing allergies can lower the risk of many disorders.

How is pulmonary fibrosis diagnosed?

Doctors use high‑resolution CT scans, pulmonary function tests, and sometimes lung biopsies to identify the characteristic scarring.

Is CPAP the only treatment for sleep apnea?

CPAP is the most effective, but oral appliances, positional therapy, weight loss, and surgery are alternatives for certain patients.

When should I see a doctor about shortness of breath?

If breathlessness comes on suddenly, worsens quickly, or is accompanied by chest pain, bluish lips, or fainting, seek emergency care. Otherwise, schedule a routine appointment if it interferes with daily activities.

Breathing disorders, though diverse, share a common physiological thread that begins with the mechanics of the diaphragm and ends with gas exchange in the alveoli.

October 18When the diaphragm contracts, negative pressure draws air into the bronchial tree, a process that is elegantly simple yet vulnerable to obstruction at multiple levels.

In obstructive diseases such as asthma and COPD, the airway lumen narrows, increasing resistance and forcing the respiratory muscles to work harder during exhalation.

Asthma distinguishes itself by the reversibility of bronchoconstriction, often triggered by allergens, cold air, or exercise, and it responds well to short‑acting β‑agonists.

COPD, by contrast, is marked by irreversible destruction of alveolar walls-emphysema-and chronic mucus hypersecretion, leading to a characteristic barrel‑shaped chest and a relentless decline in FEV1.

Restrictive disorders, including pulmonary fibrosis, impose stiffness on the lung parenchyma, limiting tidal volume and causing a shallow breathing pattern that can be mistaken for weakness.

The fibrotic process replaces compliant tissue with collagen, thereby reducing the surface area available for diffusion of oxygen and carbon dioxide.

Neuromuscular conditions, although rarer, compromise the strength of the diaphragm and intercostal muscles, turning even a normal airway into a bottleneck for ventilation.

Sleep‑related breathing disorders add another layer of complexity, as periodic airway collapse during sleep can cause intermittent hypoxia and sympathetic over‑activation.

Obstructive sleep apnea is often linked to obesity and anatomical narrowing, while central sleep apnea reflects a failure of the brainstem respiratory centers to generate appropriate rhythmic signals.

Across all these conditions, the body attempts compensation by increasing respiratory rate, recruiting accessory muscles, and, in chronic cases, altering hemoglobin affinity for oxygen.

Clinically, this compensation manifests as tachypnea, use of accessory muscles, and in severe cases, cyanosis or digital clubbing.

Early detection hinges on recognizing subtle symptom patterns such as nocturnal cough, exercise‑induced dyspnea, or unexplained fatigue.

Objective testing-spirometry for obstruction, diffusion capacity for fibrosis, and overnight polysomnography for apnea-provides quantitative confirmation of the underlying pathology.

Treatment strategies, while disease‑specific, universally aim to reduce airway inflammation, improve gas exchange, and support the patient’s functional capacity.

Ultimately, a nuanced understanding of the interplay between airway caliber, lung elasticity, and neural control empowers both clinicians and patients to intervene before irreversible damage sets in.

Karla Johnson