When a generic drug company wants to bring a cheaper version of a brand-name medicine to market, it doesn’t just need to make the pill. It needs to win a legal battle first - and that battle almost always ends up in one court: the Federal Circuit Court. This isn’t just any appeals court. It’s the only court in the U.S. that hears every patent appeal, including the most complex ones involving drugs. For pharmaceutical companies, whether they’re making brand-name medicines or generics, the Federal Circuit’s rulings decide who gets to sell what, when, and for how long.

Why the Federal Circuit Has Total Control Over Drug Patents

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit was created in 1982 to fix a mess. Before then, patent cases were scattered across 12 regional circuit courts. One court in California might rule one way on a drug patent, while a court in New York ruled differently. That created chaos for drug makers trying to plan their business. The solution? Centralize all patent appeals in one place. Since then, every single patent case in the U.S. - no matter where it started - ends up in the Federal Circuit. This isn’t just about convenience. It means the court has built up unmatched expertise in patent law, especially for pharmaceuticals. It doesn’t handle criminal cases, family law, or tax disputes. It only deals with patents, trademarks, and government contracts. That focus lets judges and clerks become true specialists. They know the difference between a compound patent and a dosing patent. They understand how the FDA’s Orange Book works. They’ve seen hundreds of cases where a company files an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) to launch a generic version of a drug like Humira or Enbrel.ANDA Filings and the Nationwide Jurisdiction Rule

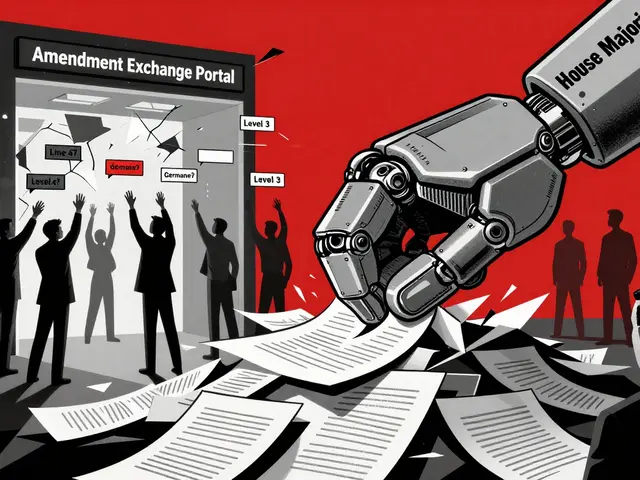

One of the biggest shifts came in 2016, in a case involving Mylan. The court ruled that when a generic drug company files an ANDA with the FDA, it’s not just asking for permission to sell a drug - it’s announcing its intent to sell that drug everywhere in the U.S. That means the patent holder can sue that company in any federal district court, even if the generic company has no office or warehouse there. Before this ruling, patent holders had to sue in places where the generic company actually did business. Afterward, Delaware became the go-to court for these cases. Why Delaware? Because it has a reputation for being fast, predictable, and friendly to patent holders. Between 2017 and 2023, 68% of all ANDA lawsuits were filed there. That’s up from just 42% in the decade before. For generic drug makers, this means they can’t avoid lawsuits by operating out of Texas or Ohio. Filing an ANDA opens the door to litigation anywhere. This rule applies to biosimilars too. In the Samsung Bioepis case, the court extended the same logic to complex biologic drugs. If you’re trying to copy a drug like Humira, your ANDA filing gives patent holders the right to sue you in any state. That’s a huge cost and risk for generic companies. Legal fees for a single ANDA case have jumped from $5.2 million to $8.7 million since 2016.The Orange Book and What Patents Can Be Listed

The Orange Book - officially titled Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations - is the secret weapon of brand-name drug companies. It’s a public list maintained by the FDA that shows which patents cover a drug and who owns them. If a patent is listed there, generic companies must either wait until it expires or challenge it in court. In December 2024, the Federal Circuit made a key ruling in Teva v. Amneal. It said a patent can only be listed in the Orange Book if it actually claims the drug itself. If a patent is for a method of manufacturing the drug, or for a packaging design, it doesn’t belong on the list. That ruling forced companies to clean up their lists. Many patents that were previously used to delay generics were removed. Now, companies spend extra time mapping their patents to the exact drug compound. A 2024 survey of top pharmaceutical firms found that pre-listing legal reviews now take 17 more business days than before. That’s time and money spent to make sure every patent on the list can survive a court challenge.

Why Dosing Patents Are Harder to Get - and Harder to Defend

A lot of pharmaceutical patents aren’t for new drugs. They’re for new ways to take old drugs. Take a drug like aspirin. You could patent a new dose: "Take 100 mg once daily instead of 325 mg three times a day." That’s called a dosing regimen patent. For years, companies used these to extend their market exclusivity. But the Federal Circuit has cracked down. In April 2025, it ruled in ImmunoGen v. a generic company that dosing changes alone rarely make a patent valid. The court said: if the drug itself was already known, and the only difference is the dose or schedule, then it’s obvious - unless you can prove something unexpected happened. For example, if a lower dose suddenly reduced side effects by 70% instead of just 10%, that might be enough. But if the results are just what you’d expect, the patent gets thrown out. This decision changed how companies file patents. A 2024 analysis by Clarivate showed that after this ruling, pharmaceutical companies cut their dosing regimen patent filings by 37%. Instead, they’re investing more in truly new chemical compounds. The court’s message is clear: don’t try to game the system with tiny tweaks. If you want a patent, make something new.Standing: Can You Sue Before You Even Start?

Here’s a tricky part: can a generic company challenge a patent before it even starts developing the drug? The answer used to be no. You had to show you were actively making the drug. But in May 2025, the court ruled in Incyte v. Sun Pharmaceutical that companies can challenge patents earlier - if they can prove they’re close to launching. The court now requires "concrete plans" and "immediate development activities." That means you need to show Phase I clinical trial data, manufacturing plans, or signed supplier contracts. Just saying "we’re thinking about it" isn’t enough. This gives generic companies a chance to clear patent roadblocks before spending hundreds of millions on development. But it also means they have to document everything - from lab notebooks to board meeting minutes - to prove they’re serious. Some judges, like Judge Hughes, have warned that this standing rule might be too strict. He noted in his concurrence that the court has dismissed too many cases where generic companies clearly had a financial interest in challenging patents. That’s why Congress is now looking at the "Patent Quality Act of 2025," which could lower the bar for standing in drug patent cases.

The Federal Circuit isn't just a court-it's a silent gatekeeper of life-saving medicine. Every ruling they make ripples out to pharmacy shelves, to people choosing between insulin and rent. And yet, nobody talks about it outside legal circles. That’s the real tragedy: the system that decides who lives and who doesn’t is run by judges who’ve never had to pay for a prescription.

December 8It’s not about innovation anymore. It’s about who can afford the lawyers. The Orange Book? More like a lockbox for corporate greed. And dosing patents? Pathetic. You don’t patent a schedule-you patent a molecule. That’s basic.

They call it expertise. I call it isolation. One court, one mindset, one outcome: profit first, patients last.

Suzanne Johnston