Most people have never heard of Wilson’s disease - until it hits their family. It’s rare, affecting about 1 in 30,000 people, but when it shows up, it doesn’t mess around. This isn’t just a liver problem. It’s a silent copper bomb ticking inside the body, slowly poisoning the liver, brain, and eyes. And if you don’t catch it early, it can kill you. But here’s the thing: Wilson’s disease is treatable. Not just manageable - treatable. With the right therapy, people live full, normal lives. The key is understanding how copper goes wrong, and how we fix it.

What Actually Goes Wrong in Wilson’s Disease?

Your body needs copper. It’s in your enzymes, your nerves, your blood. But it’s like salt - too much, and it ruins everything. In Wilson’s disease, a broken gene called ATP7B stops your liver from doing its job. Normally, your liver uses this gene to pack copper into a protein called ceruloplasmin and flush the rest out through bile. In Wilson’s disease, that system fails. Copper doesn’t get packaged. It doesn’t get flushed. It just piles up.At first, the liver tries to hide the damage. Metallothionein, a natural copper sponge, soaks up the extra metal. You feel fine. Liver tests might be slightly off, but doctors often mistake it for fatty liver or even autoimmune hepatitis. That’s why the average person waits over two years before getting the right diagnosis. By then, copper has leaked into the bloodstream. Free copper - the dangerous kind - starts drifting to the brain, kidneys, and eyes.

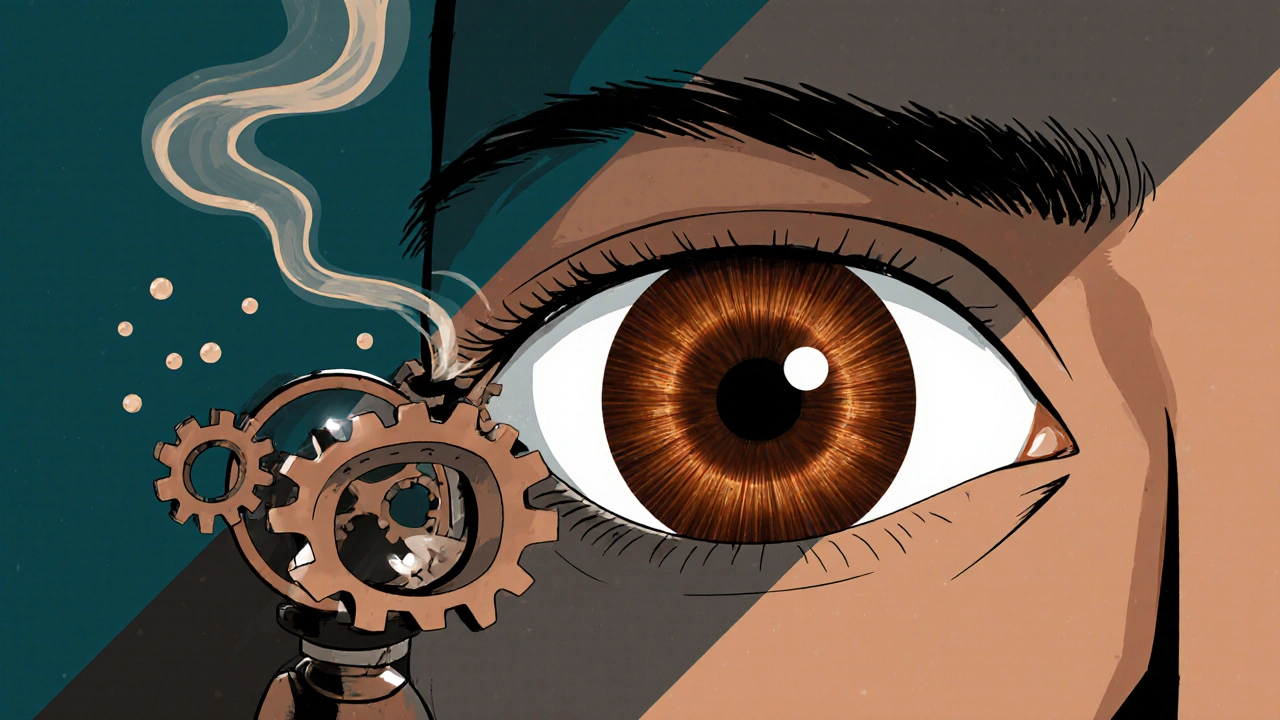

The eyes give it away. Over 95% of people with neurological symptoms develop Kayser-Fleischer rings - a rusty brown halo around the iris. It’s not visible to the naked eye unless you’re looking for it. An eye doctor with a slit lamp can spot it in seconds. That’s often the first real clue. But even then, many patients are told it’s just aging or something else. The real giveaway? Low ceruloplasmin in the blood (under 20 mg/dL) and high copper in the urine (over 100 μg/24 hours). Most people with liver symptoms have this combo. Those with brain symptoms? Not always. That’s why testing both is critical.

Why Chelation Therapy Isn’t Just a Pill - It’s a Lifeline

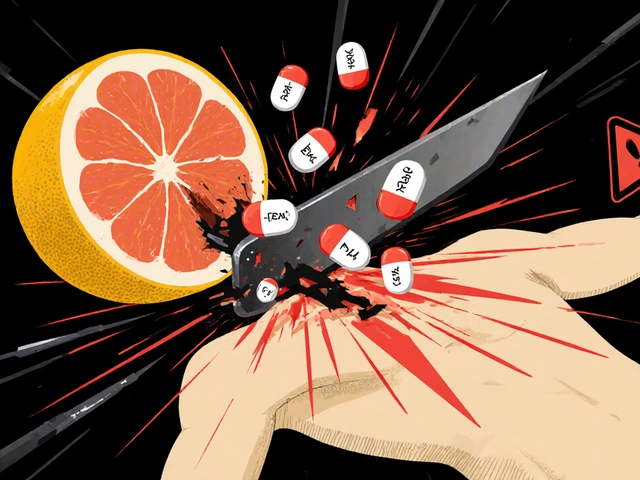

Once you’re diagnosed, time becomes your enemy. Copper keeps building. Brain damage can be permanent. That’s where chelation therapy comes in. Chelators are molecules that grab copper like a magnet and pull it out of your body through urine. The two main ones are D-penicillamine and trientine.D-penicillamine has been around since the 1950s. It’s cheap - about $300 a month in the U.S. - and effective. But it’s brutal. Around half of patients get worse before they get better. Neurological symptoms like tremors, slurred speech, or stiffness can spike in the first few weeks. That’s not a fluke. It’s the copper being shaken loose from tissues and swirling through the brain. Many patients end up in the hospital during this phase. That’s why doctors now pair it with zinc from day one - zinc blocks copper absorption in the gut and slows the flood.

Trientine is the smoother option. It’s less likely to cause neurological flare-ups. But it costs nearly six times more - around $1,850 a month. Insurance doesn’t always cover it. For many, that’s a dealbreaker. Then there’s zinc acetate. It doesn’t pull copper out. It stops new copper from entering. That’s why it’s the go-to for maintenance after the initial chelation. You take it three times a day, on an empty stomach. It’s not glamorous, but it keeps copper levels stable for life.

And then there’s the new stuff. In 2023, a drug called WTX101 showed 91% success in stopping brain damage in early trials - better than trientine. It’s not widely available yet, but it’s the future. Another new drug, CLN-1357, dropped free copper by 82% in 12 weeks with zero neurological side effects. These aren’t just lab results. They’re hope.

The Real Battle: Diet, Side Effects, and Lifelong Monitoring

Chelation isn’t the whole story. You also have to eat differently. The goal: under 1 mg of copper per day. That means saying no to shellfish, organ meats, nuts, chocolate, mushrooms, and even some tap water (if it runs through copper pipes). It’s not impossible, but it’s exhausting. One patient on a support forum said, “I stopped eating almonds because I was scared. Then I realized I was eating them in granola bars. I had to read every label.”Side effects are brutal. D-penicillamine can cause lupus-like rashes, kidney damage, or even bone marrow suppression. Trientine often leads to iron deficiency - you end up needing iron supplements just to stay upright. Zinc causes nausea, metallic taste, and low copper levels if you overdo it. And you have to take these pills on an empty stomach. No food for two hours before and after. That’s hard when you’re a student, a parent, or working two jobs.

And you can’t stop. Ever. One missed dose can let copper creep back. That’s why monitoring is non-negotiable. Every three months: blood tests for liver enzymes, free copper, and ceruloplasmin. Every six months: a 24-hour urine copper test. The target? Between 200 and 500 μg/24h. Too low, and you risk copper deficiency. Too high, and you’re back to organ damage.

And yet, 35% of patients miss doses. Why? Side effects. Cost. Complexity. A woman in Manchester told me, “I had to choose between paying for my meds and feeding my kids. I skipped a week. My tremors came back worse.”

How Is This Different From Other Liver Diseases?

You might hear about fatty liver or hepatitis. Those are common. Wilson’s is not. And that’s why it’s missed. In autoimmune hepatitis, your immune system attacks your liver. Ceruloplasmin is normal. Urine copper is low. In Wilson’s, it’s the opposite. The liver isn’t being attacked - it’s failing at its job. That’s why a simple blood test for ceruloplasmin and urine copper can rule it in or out.And it’s not just the liver. Menkes disease is the opposite - a copper deficiency that kills babies. Indian childhood cirrhosis looks like Wilson’s on the liver, but no brain damage, no eye rings. That’s why you need the full picture: symptoms, blood, urine, eye exam, and genetic testing. One test alone won’t cut it.

What’s the Future Looking Like?

The future is better than it’s ever been. Gene therapy trials are underway. Scientists are inserting a working copy of the ATP7B gene into liver cells using harmless viruses. Early results in six patients showed no major side effects. It’s not a cure yet, but it’s the first real shot at fixing the root cause - not just managing the mess.Diagnostic tools are improving too. In 2023, experts lowered the urine copper threshold for diagnosis from 100 to 80 μg/24h in liver cases. That catches more people earlier. Genetic testing is now part of the standard scorecard. If you have two broken copies of ATP7B, you have Wilson’s - no guesswork.

And awareness is growing. More doctors are testing for it when liver enzymes are high and no other cause shows up. More eye doctors are checking for Kayser-Fleischer rings. More patients are speaking up. The average diagnosis delay is still 2.7 years - but it’s dropping. In Europe, 85% of patients get the right treatment. In the U.S., it’s 65%. That gap is closing.

Wilson’s disease used to be a death sentence. Now, with early detection and consistent treatment, life expectancy is normal. You can work. You can have kids. You can live. But it takes vigilance. It takes listening to your body. It takes pushing for tests when something feels off.

If you’ve had unexplained liver issues, tremors, or a family history of liver disease - ask for the copper tests. Don’t wait for a diagnosis. Demand it.

Can Wilson’s disease be cured?

No, Wilson’s disease can’t be cured yet - but it can be controlled for life. With consistent chelation therapy and monitoring, copper levels stay safe, organ damage stops, and people live full lives. Gene therapy is in early trials and may one day offer a true cure, but it’s not available yet.

How do I know if I have Wilson’s disease?

If you have unexplained liver problems, neurological symptoms like tremors or trouble speaking, or psychiatric changes, ask for three tests: serum ceruloplasmin, 24-hour urinary copper, and a slit-lamp eye exam for Kayser-Fleischer rings. Genetic testing for ATP7B mutations confirms it. Don’t wait - early diagnosis saves your liver and brain.

Is chelation therapy dangerous?

It can be, especially at first. D-penicillamine often worsens neurological symptoms in the first few weeks. That’s why doctors now start with zinc alongside it. Trientine is safer but more expensive. Side effects like nausea, rashes, or low iron are common. But the danger of not treating - liver failure, brain damage, death - is far worse. Monitoring keeps it safe.

Can I eat normally with Wilson’s disease?

No - you need a low-copper diet. Avoid shellfish, liver, nuts, chocolate, mushrooms, and lentils. Drink bottled water if your pipes are copper. Read labels. Many multivitamins and protein powders have added copper. Aim for under 1 mg per day. It’s strict, but doable. A dietitian who knows Wilson’s can help you plan meals that are safe and nutritious.

How often do I need blood and urine tests?

During active treatment, get blood tests every 3 months (liver enzymes, free copper, ceruloplasmin). Do a 24-hour urine copper test every 6 months. Once stable, you might space them out, but never stop. Copper creeps back fast. Missing tests is how people end up back in the hospital.

What happens if I miss my medication?

Copper starts building again within days. Even one missed week can trigger symptoms. If you miss a dose, take it as soon as you remember - but don’t double up. If you miss multiple doses, contact your doctor. You may need a urine test to check if copper levels are rising. Consistency isn’t optional - it’s survival.

Can Wilson’s disease affect my children?

Yes - it’s inherited. If you have Wilson’s, each child has a 25% chance of getting it. Siblings should be tested, even if they feel fine. Kids as young as 5 can show symptoms. Early testing with copper and genetic tests can catch it before damage happens. Don’t wait for symptoms.

Just read this after my cousin got diagnosed last year. I had no idea copper could do this. The part about the eye rings? Mind blown. I thought it was just some weird art project she was into.

November 23Katy Bell