People often hear the term affirmative consent and assume it applies to all kinds of permission - including medical treatment. But that’s not true. Affirmative consent laws were never designed to govern who can make medical decisions for an incapacitated patient. They were created to define what counts as legal sexual consent on college campuses and in state criminal codes. Mixing these two ideas leads to real confusion - and sometimes dangerous misunderstandings in healthcare settings.

What Affirmative Consent Actually Means

Affirmative consent means clear, voluntary, and ongoing agreement during sexual activity. It’s not just the absence of a "no." It’s an active "yes." This standard was first adopted in California in 2014 under Senate Bill 967 and has since been copied by 13 other states. The idea is simple: if someone isn’t saying yes - or if they’re passed out, too drunk, or pressured - then there’s no consent. It’s about stopping sexual assault by making sure every step is clearly agreed to.

These laws are used in campus disciplinary hearings, criminal cases, and Title IX investigations. They require proof of active participation - words, gestures, or actions that show willingness. Silence doesn’t count. Nodding while unconscious doesn’t count. Consent can be withdrawn at any time. That’s the core of it.

Medical Consent Has Nothing to Do With This

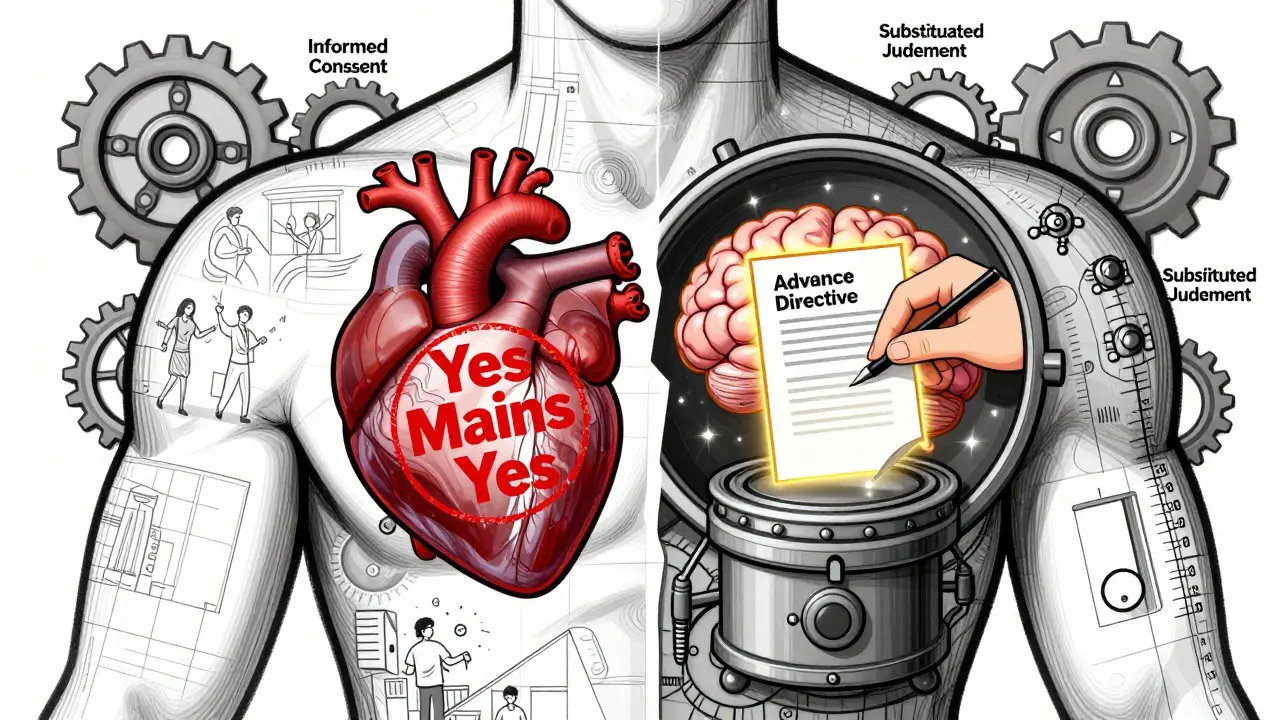

When a patient can’t speak for themselves - because they’re unconscious, in a coma, or have dementia - medical teams don’t ask for "affirmative consent." They follow a completely different legal system called informed consent and substituted judgment.

Informed consent means doctors must explain what’s wrong, what treatment they’re suggesting, what the risks and benefits are, what other options exist, and what happens if you do nothing. Then the patient - if they’re capable - says yes or no. This isn’t new. It goes back to a 1914 court case, Schloendorff v. Society of New York Hospital, where a patient was operated on without permission. The court ruled: every person has the right to decide what happens to their body.

That principle still stands today. In California, Civil Code Section 56.11 says doctors must disclose all "material risks." In New York, it’s codified in Public Health Law. In every state, the rule is the same: no treatment without understanding and agreement.

What Happens When a Patient Can’t Decide?

If someone can’t give informed consent - say, after a stroke or severe brain injury - the law doesn’t switch to "affirmative consent." Instead, it uses substituted judgment.

Substituted judgment means someone else - usually a spouse, adult child, or legally appointed guardian - makes the decision based on what the patient would have wanted. Not what the family thinks is best. Not what’s easiest. But what the patient, if they could speak, would have chosen.

How do they know? By looking at past conversations, written advance directives (like a living will), religious beliefs, or how the person lived their life. If a patient once said, "I never want to be hooked up to machines if I’m not going to get better," that guides the decision.

California Health and Safety Code Section 7185 spells this out clearly. It says surrogates must act according to the patient’s known wishes. If those aren’t known, then they must act in the patient’s "best interest." But even then, it’s not about asking for a verbal "yes" right then and there. It’s about making a judgment based on history, values, and medical facts.

Why People Get Confused

There’s a reason so many think these are the same thing. Both use the word "consent." Both involve permission. Both are about autonomy. But that’s where the similarity ends.

On college campuses, students hear about affirmative consent in sexual assault prevention workshops. They hear it in dorm meetings, health center flyers, and orientation videos. Then they go to the hospital. Their parent is in the ICU. The doctor says, "We need consent for this surgery." And suddenly, the student thinks: "Wait - do I need to get a verbal yes from Mom right now?"

That’s not how it works. The hospital isn’t asking for a live "yes" like a college party. It’s asking if there’s an advance directive. If there’s a healthcare proxy. If the family knows what the patient would have wanted.

A 2023 survey at the University of Colorado Denver found that 78% of undergraduates couldn’t tell the difference between medical consent and sexual consent. That’s not their fault. The terms are used in overlapping spaces - but they’re not interchangeable.

Real Consequences of Mixing Them Up

Confusing these two systems can cause harm. Imagine a family insists on a feeding tube for a loved one who once said, "I don’t want to be kept alive like a vegetable." But because they don’t have a written directive, and because they think "affirmative consent" means they need to "get permission" right now, they push for treatment anyway - out of guilt, fear, or misunderstanding.

Or imagine a doctor, trying to be extra careful, asks a confused family member to say "yes" out loud before giving pain medication. That’s not just unnecessary - it’s unprofessional. Medical ethics don’t require that. They require understanding, documentation, and respect for prior wishes.

Even worse, some hospitals have started training staff to use "yes means yes" language in medical settings - not realizing they’re misapplying a legal standard meant for sexual assault cases. The American Medical Association warned against this in its 2023 update to Opinion E-2.225: "Physicians should not apply sexual consent standards to medical decision-making processes. Doing so creates unnecessary barriers to urgent care and misunderstands the legal foundations of medical consent."

What You Should Do Instead

If you want to make sure your wishes are followed if you ever can’t speak for yourself:

- Write an advance healthcare directive. This is a legal document that says what treatments you want or don’t want.

- Designate a healthcare proxy - someone you trust to speak for you if you can’t.

- Talk to that person. Not once. Talk often. Tell them your values, your fears, your beliefs about life, death, and suffering.

- Keep a copy in your phone, with your lawyer, and give one to your doctor.

Don’t wait for a crisis. Most people only think about this after someone they love is in the hospital - and by then, it’s too late to make clear choices.

The Bottom Line

Affirmative consent laws are about sex. They’re not about surgery, medication, or life support. Medical decisions follow a different path - one built on decades of legal precedent, ethical codes, and patient rights. You don’t need someone to say "yes" right now to get care. You need to have planned ahead.

Understanding this difference isn’t just academic. It’s personal. It’s about protecting your autonomy when you can’t speak for yourself. And it’s about making sure the people you love aren’t left guessing - or worse, making decisions based on a law that doesn’t even apply to them.

Are affirmative consent laws used in hospitals?

No. Affirmative consent laws apply only to sexual activity, not medical treatment. Hospitals use informed consent and substituted judgment standards, which are based on patient history, advance directives, and legal surrogates - not on verbal affirmations in real time.

Can a family member give consent for my medical treatment if I’m unconscious?

Yes, but only if they’re legally authorized - like a healthcare proxy named in your advance directive, or a close family member under state law. They must make decisions based on what you would have wanted, not what they think is best. If no directive exists, they act in your best interest.

What’s the difference between informed consent and affirmative consent?

Informed consent requires a healthcare provider to explain risks, benefits, and alternatives so the patient can make a decision. Affirmative consent requires active, ongoing verbal or physical agreement during sexual activity. One is about disclosure and understanding. The other is about clear, enthusiastic participation.

Do I need to sign a form every time I get treatment?

Not always. For routine care - like getting a flu shot - a simple verbal agreement is enough. For major procedures - like surgery or chemotherapy - you’ll sign a form. But the key isn’t the signature. It’s that you understood what you were agreeing to. If you didn’t, the consent isn’t valid.

Can a minor give consent for medical treatment?

Yes, in certain cases. In California, minors 12 and older can consent to treatment for STDs, HIV, mental health, and substance abuse without parental permission. This is based on public health needs, not affirmative consent laws. It’s a separate legal exception designed to protect vulnerable youth.

What if my family disagrees about what I would have wanted?

If there’s no advance directive and family members disagree, hospitals often turn to ethics committees. In some states, a court may need to appoint a guardian. The goal is to honor your known wishes, not to let conflict delay care. That’s why having a written plan is so important - it removes guesswork.

Finally, someone clarified this properly. I’ve seen so many people panic in hospitals thinking they need to say "yes" out loud for every treatment. It’s exhausting.

January 16Crystel Ann